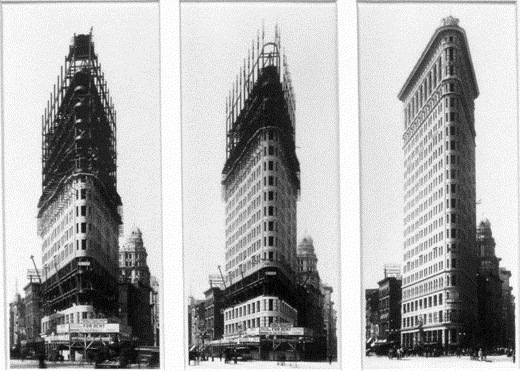

The wedge-shape Flatiron Building is one of the best-known and most beloved symbols of New York City. When TV shows and movies need to establish that their proceedings are based in Manhattan, a shot of the 22-story triangular structure is de rigueur; in the Spider-Man movies, Peter Parker’s employer, the “Daily Bugle,” is located here. The building was designated a New York City Landmark in 1966, added to the National Register of Historic Places 13 years later, and decreed a National Historic Landmark in 1989—and of course, an entire neighborhood was named after it.

Yet when the Flatiron Building was unveiled in June 1902, it was greeted by a fair amount of derision. “The New York Times” labeled it a “monstrosity,” and many worried that its three-sided structure, little more than six feet wide at its front, would be knocked down by strong gusts of wind. Sculptor William Ordway Partridge, whose works include “The Pietà” at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, went so far as to dub the building “a disgrace to our city, an outrage to our sense of the artistic, and a menace to life.”

Architect Daniel Burnham opted for the triangular shape to maximize the building’s footprint on the triangular parcel of land set amid Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and 22nd and 23rd Streets. At the time, the scrap of land itself was known as the Flat Iron; the building being erected on it was called the Fuller Building, as it was intended to be the headquarters of the Fuller Company, a construction firm. Ten years earlier, building the 285-foot-high structure in New York would have been, if not impossible, then highly unfeasible. Steel skeletons are what allowed tall buildings to be built safely and affordably, but until 1892, the city required buildings to include masonry in its structure.

Not only was the Flatiron Building one of New York’s first skyscrapers, it was also the first steel-skeleton structure whose construction was visible to the public. The structural engineers reinforced the frame to ensure that the slender building would withstand any gusts in what was already a bit of a wind tunnel. All the same, the relative speed with which the building was erected—once the foundation was completed, the structure proceeded at a rate of a floor a week—probably did not assuage the fears of those observing the construction.

Nonetheless, once the building was completed, and despite the carping of numerous critics, the public took pride in what was the first skyscraper north of 14th Street. Photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen and artists Childe Hassam and Albert Gleizes are among those who created works in homage to the Flatiron. While its shape was the building’s original talking point, its Renaissance-inspired Beaux-Arts facade was worthy of attention too. Made of limestone and glazed terra cotta, it features columns, medallions, balustrades, friezes, and along the 22nd floor, gargoyles.

The facade of the Flatiron Building. Image: User Totya/Wikimedia

One thing the building did not originally have were bathrooms for women; no doubt Fuller Company did not expect women to frequent its headquarters. To accommodate female visitors, management eventually designated the bathrooms on the odd-number floors for women, with those on the even-number floors reserved for men.

Fuller Company occupied the 19th floor of the building only until 1910, eventually moving uptown to the structure on 57th Street that now bears the Flatiron’s intended name, the Fuller Building. Other tenants throughout the Flatiron Building’s history included the Imperial Russian Consulate, the Murder Inc. crime syndicate, and Taverne Louis, one of the first restaurants catering to whites to hire an African American jazz band, Louis Mitchell and the Southern Symphony Quintette, to perform. St. Martin’s Press and other imprints of Macmillan publishing company are among the current tenants.

Walls of the 23rd Street subway station adorned with windblown hats. Image: Chris Sampson/Flickr

As well as being an instantly recognizable icon of New York, the Flatiron Building is credited with popularizing the term “23 skidoo.” The addition of the skyscraper to what was already a windy spot resulted in some impressive downdrafts and updrafts. These gusts would sometimes lift the skirts of many women walking to and from the upscale emporia of Ladies’ Mile along Fifth Avenue. Boys and men would loiter around the Flatiron in hopes of catching a glimpse of ankle, calf, or knee; policemen patrolling the area would shout “23 skidoo.” Both “23” and “skidoo” were already slang for “get out of here,” but the combination of the two, perhaps a reflection of the building’s nose facing 23rd Street, is believed to have originated here. Those gusts are also why the 23rd Street station of the N/Q/R subway lines features mosaics of 120 windblown hats along its tiled walls.