Today Gansevoort Street is considered the southern border of the Meatpacking District. But before the Whitney Museum of American Art and dozens of exclusive shops and eateries took up residence, before it was the site of abattoirs and tenements, and before it was the locale of an Army fort, Gansevoort Street housed a Lenape trading post. Located roughly where Gansevoort now meets Washington Street, the post was part of a village named Sapokanikan, or “Land Where the Tobacco Grows,” which made up much of what is now Greenwich Village.

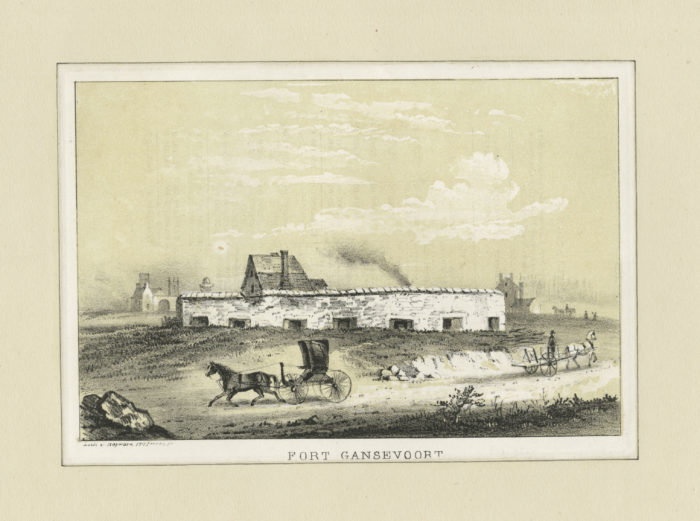

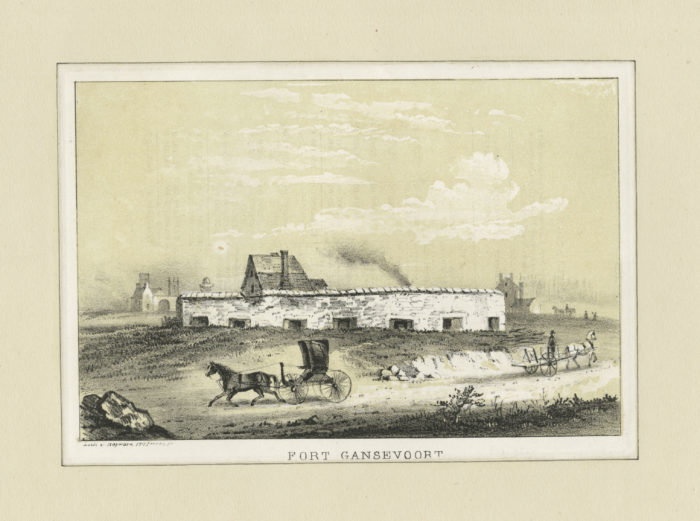

When the Dutch settled into lower Manhattan in the 17th century, they built a kiln alongside the Native American trail to the trading post and dubbed the roadway Old Kill Road, “kill” having been a synonym for “kiln.” The street’s current name is also Dutch and translates to “Geese Ford,” but the street was never a pathway for fowl. The street was named after Fort Gansevoort, built at what is now Gansevoort and 12th Avenue in 1812 to defend the nascent United States from the British ships on the Hudson River during the War of 1812. The fort, which included 22 mounted guns, was in turn named after Peter Gansevoort, a colonel in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War (and a grandfather of “Moby-Dick” author Herman Melville).

Fort Gansevoort. Image: New York Public Library/public domain/Wikimedia

The fort, which saw no action in the war, was torn down in the mid-19th century, though an art gallery of the same name moved in nearby in 2015. The fort was razed to make way for the terminus of the Hudson River Railroad, whose tracks, abandoned a century later, are now the foundation of the High Line. By this time the street was paved with its distinctive Belgian blocks; these are larger and more regular in shape than cobblestones. Also around this time townhouses, stores, warehouses, and factories were beginning to be built on the street.

The first “French flats,” the original term for upscale apartment houses, were built on Gansevoort in the 1870s, though they soon were quickly outnumbered by tenements housing the workers employed at the nearby railroad and factories. In 1879 the Gansevoort Market opened at Washington Street, the site of the Lenape trading post. This open-air produce market became so well known that the surrounding neighborhood was called by that name.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/be/Gansevoort_Street%2C_No._53%2C_Manhattan_%28NYPL_b13668355-482675%29.tiff

An iconic photo of 53 Gansevoort Street, taken by Berenice Abbott in 1936. Image: public domain/Wikimedia

In fact, it was not until the early 20th century that the neighborhood became known as the Meatpacking District. By 1900 more than 250 slaughterhouses and packing plants had set up shop in the area, though none were on Gansevoort itself until several decades later.

Gansevoort Market was turned into a meat distribution center for the area in 1950. Soon after, though, the meat processing and packing industry became less localized, thanks to refrigeration, supermarkets, and improved transportation. By the 1980s many of the meat-related businesses had closed up shop or moved up the Bronx. Nightspots, some less salubrious than others, moved into a number of the now-empty warehouses and factories. Some of the more cutting-edge clubs, however, attracted artists, who appreciated the relatively affordable rents of the former tenements, and trendsetters who viewed the remaining unoccupied buildings—of which there were still many—as ripe for conversion into boutiques and eateries.

Bridging the gap between the down-on-its-heels Meatpacking District and the glossy neighborhood it is today was Florent. In 1985 a French restaurateur named Florent Morellet took over the abandoned R&L Restaurant, a diner that had been frequented by meatpacking workers, and transformed it into a round-the-clock eatery dishing up comfort food with panache. While regulars included designer Diane von Fürstenberg and artist Roy Lichtenstein, who ate at the same table every day, shift workers and club kids alike were welcomed with the same joie de vivre. The HIV-positive Morellet was also something of a hero in the LGBT community; among other things, he posted his T-cell count on the wall chalkboard along with the day’s specials.

The Whitney Museum. Image: Beyond My Ken/Wikimedia

Florent was in some ways a victim of its success in helping to turn the neighborhood into a desirable destination: Rent increases forced Morellet to close the restaurant in 2008. Today the building, its R&L Restaurant sign intact, is home to a Madewell clothing store. The most notable occupant of Gansevoort Street today is the Whitney Museum, which moved here from the Upper East Side in 2015. The 50,000-square-foot building designed by Renzo Piano is surrounded by 13,000 square feet of outdoor exhibition space and terraces whose views of the High Line, the Hudson, and the New York skyline rivals the artworks inside. Its permanent collection consists of more than 23,000 20th– and 21st-century works by more than 3,000 American artists.

Spring equinox as seen from Gansevoort Street. Image: WindingRoad/Wikimedia

Gansevoort Street has one additional claim to fame. It aligns almost perfectly with the sun during the spring and autumn equinoxes. Locals and those who live in other parts of the city flock to Gansevoort on those dates to photograph the setting sun seemingly nestled between the buildings flanking the street. It is unknown whether the Lenape chose this location as the site of its trading post for that reason or whether it was a coincidence, but as the street and the neighborhood continue to evolve, one might want to believe that the locale was intentional, and that these picture-perfect vistas are celestial reminders of the area’s origins.