The SoHo Cast-Iron Historic District and Extension are home to the largest collection of full and partial cast-iron buildings in the world. This revolutionary building method changed the face of New York City in the 1800s and created some of the most beautiful structures in Lower Manhattan.

For centuries, wrought iron was the most popular form of metal building material due to its relative ease of manufacture. Cast iron (heated to liquid to rid it of impurities and cast it in molds) requires much higher temperatures than wrought iron (heated until malleable and hammered into shape). By experimenting with heating methods around 1775, Abraham Darby of England made the process of casting iron economically feasible for building projects. Soon, the process gained popularity in the manufacture of decorative architectural elements, and later structural components such as columns and beams. As structural support, cast iron became particularly important in the building of mills in England, where it was placed inside masonry walls, but by placing cast iron out in the open in stunning glass conservatories, greenhouses, and pavilions, the material was thrust into the limelight.

Queen Victoria at the cast-iron Crystal Palace in London circa 1851 (Image: Wikimedia)

In basic terms, cast iron building components were cast in sand molds, cleaned, filed, and painted, then shipped to construction sites where pieces were assembled. As a building material, cast iron’s primary benefit was its ability to accommodate much larger windows than was possible in masonry construction of the time. This was especially important for “show windows” in store-and-loft type buildings popular throughout Lower Manhattan in the mid-19th Century. Another benefit was the ability to create large, relatively open interior spaces propped up by cast-iron columns, allowing for warehouse storage spaces or large equipment. By providing sprawling floor plates and large windows that delivered interior light in the pre-electrification age, cast iron construction was critical to the manufacturing industry of the time and to what have become the most coveted residential spaces of today.

Cast iron had other advantages wood and masonry couldn’t match. Buildings made of cast iron were relatively easy and quick to assemble compared to masonry, not to mention much cheaper. By selecting pre-made cast iron components from a foundry, a builder could assemble a structure without the services of an architect. And a building constructed of cast iron could be disassembled and reassembled in a new location if necessary.

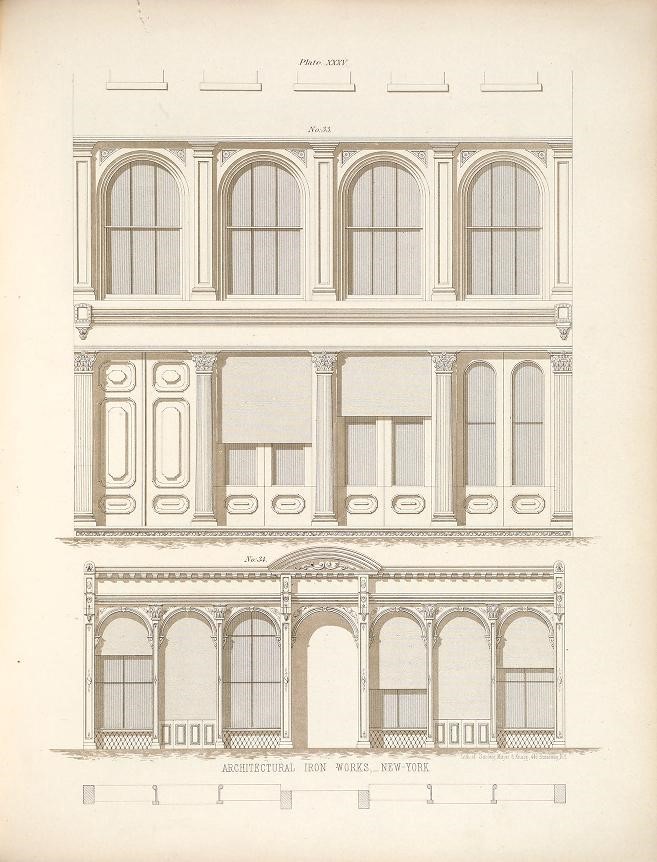

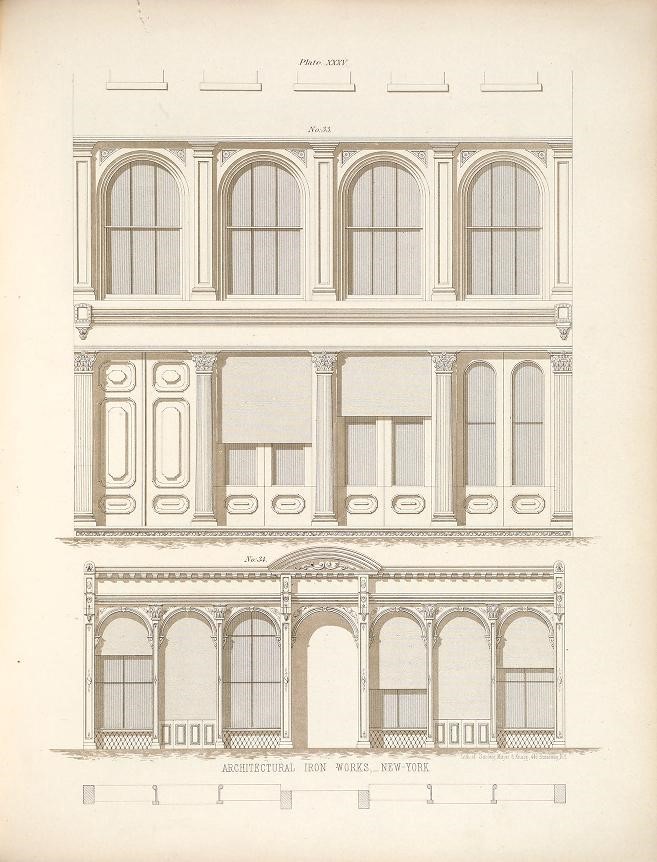

Among the innovators of New York’s cast-iron building was Daniel Badger who founded Architectural Iron Works which, in essence, created a catalog of pre-fabricated stock cast-iron pieces for order, as well as custom made-to-order offerings. Credited with greatly popularizing the building material, he can also be accused of propagating the fallacy that cast iron is fireproof. In fact, his 1865 catalog unequivocally states, “As a resistant of fire, iron is unequaled. Wherever it is used, the cost of insurance against fire will be material reduced, and it must be evident that by its use a building may be made absolutely fire-proof.”

A plate from Badger’s Architectural Iron Works 1865 catalog (Image: Internet Archive)

Of course, most buildings made of cast-iron components also included highly flammable wood interiors, which would, in turn, burn hot enough to weaken the iron. This lack of incombustibility, to use Badger’s term, in addition to changing architectural tastes were the primary reason cast iron fell largely out of favor in New York by the 1890s. And although its time was limited, cast iron is credited with many of the concepts that inform modern skyscraper construction to this day, including the adoption of standardized building units, the advent of curtain wall construction methods and ability to build vertically in a city where land prices drive living and working spaces ever skyward.

While the U.S. Capitol building’s cast-iron dome may be our country’s most famous bit of iron, the SoHo Cast-Iron Historic District (created in 1973) and Extension (created in 2010) contain the largest collection of cast-iron buildings in the world. Together the districts protect more than 600 historic structures in this revered neighborhood. Here are a few of the most remarkable.

490-492 Broadway

The E.V. Haughwout Building (Image: Wikimedia)

The E.V. Haughwout Building at the corner of Broadway and Broome Street is one of the most important examples of cast-iron construction of the period. Built in 1857, it was one of the first buildings to incorporate two cast-iron facades on a corner building. The Haughwout building was also home to the first commercial passenger elevator. In 2015, 490 Broadway was purchased for $145 million by Amancio Ortega who owns Inditex, the parent of fashion retailer Zara.

480-482 Broadway

480-482 Broadway (Image: Wikimedia)

Decorated with nine bays divided into three sections by bold Ionic columns and delicate screenwork, this handsome Richard Morris Hunt design, also known as the Roosevelt Building, cuts a handsome figure along the Broadway retail corridor. Hunt is also known as the architect behind other New York icons, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s façade and the Statue of Liberty’s base.

28 Greene Street

28 Greene Street’s breathtaking mansard roof (Image: Michael Daddino/Flickr)

Dubbed the Queen of Greene, this beautiful structure incorporates projecting central bays, a mansard roof and dormer windows. Designed in the French Second Empire style by J. F. Duckworth in 1872, the Historic District Designation Report calls it “the most powerful building on the block,” high praise for one of the most beautiful blocks in the city. The building was meticulously restored and converted to pristine luxury rentals in 2010.

469 Broome Street (55 Greene Street)

469 Broome at the corner of Greene Street (Image: Wikimedia)

Known as the Gunther Building, this corner masterpiece was designed by Griffith Thomas in 1871. The building features distinctive curved glass corner windows and rows of substantial bays. Named for its former furrier tenant, today the building is populated by a number of architectural firms, including Beyhan Karahan and Associates which spearheaded the building’s 2001 façade restoration.