The Historic Pubs of the West Village

As one of the city’s older neighborhoods, the West Village is home to some of its most historic bars. A pub crawl here is a bit like a history tour, one where you can indulge in your favorite beverages while seeing how the neighborhood has—and has not—changed over time.

Inside Julius’. Image: Steam Pipe Trunk Distribution Venue/Flickr

Julius’, on the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place, is an ideal case study. When the stolid three-story structure was built in 1826, West 10th Street was called Amos Street and Waverly Place was Factory Street. The first floor of the building was converted to a grocery in 1840; in 1864 it became a bar.

Age alone is not why Julius’ was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016, however. In the 1950s, after its Prohibition days as a speakeasy and its popularity as a gathering spot for celebrities in the 1930s and ‘40s, it began attracting a sizable gay clientele, leading to its semi-official title as the oldest gay bar in the city. (More modestly, Julius’ describes itself as “one of the oldest gay bars in the Village.”) The bar’s management hardly encouraged this clientele, however. Staff consistently kicked out those they thought were gay, saying they were obliged to do so since the state Liquor Authority declared it illegal to serve alcohol to disorderly customers and LGBT people were considered “disorderly” by default.

In protest, four members of the Mattachine Society, an early LGBT-rights group, engaged in a “sip-in” at Julius’ on April 21, 1966. The bartender’s refusal to serve them drew a great deal of media and public attention to this discriminatory practice, resulting in a court case that struck down the conflation of homosexuality with “disorderliness” and gave way to the rise of gay bars.

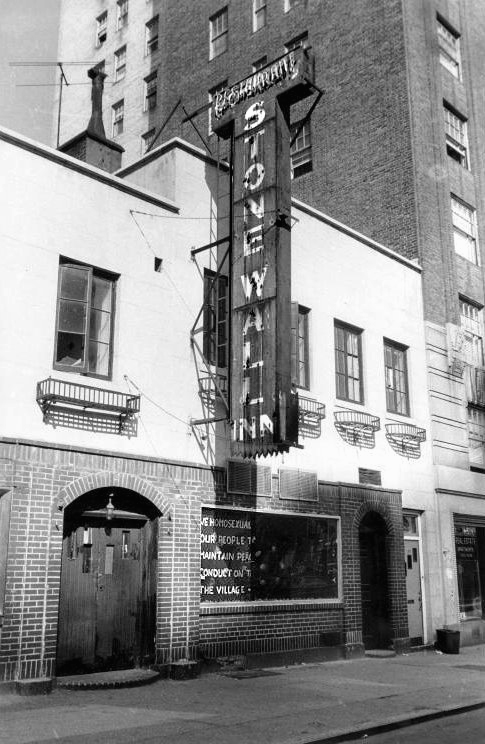

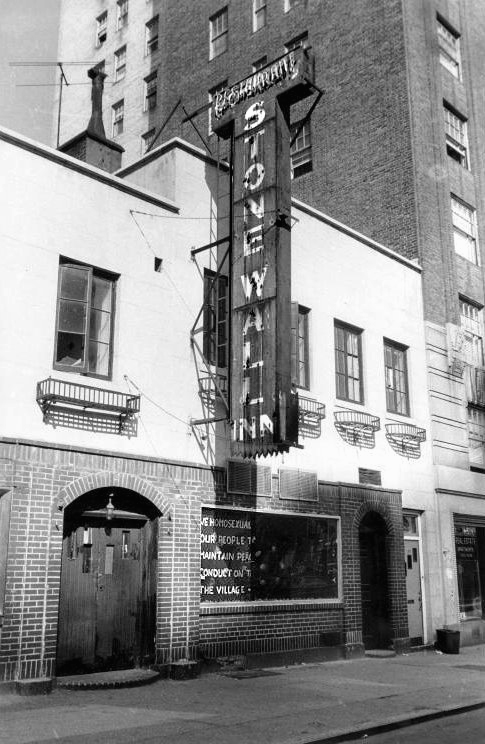

The Stonewall Inn in 1969. Image: Diana Davies/New York Public Library/Wikimedia

Julius’ contribution to LGBT rights is often overshadowed by that of the Stonewall Inn, less than two blocks away (53 Christopher Street, between Waverly Place and Seventh Avenue South). Originally a stable, the 1840s building later housed a restaurant called Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn. In 1966 it became a gay bar, arguably the largest in the country, and the only city nightspot where same-sex dancing was allowed.

The Stonewall did not have a liquor license; instead it paid off the police weekly. Nonetheless, like other LGBT establishments, it was regularly raided by the vice squad. By the time the police raided the Stonewall in the early hours of June 28, 1969, the LGBT community was ready to fight back against the harassment. Bar patrons and area residents alike yelled at, threw objects at, and physically fought the police, the situation escalating into a riot and six days of protests. This in turn rallied the LGBT community worldwide to actively fight for their rights. On the one-year anniversary of the raid, protestors marched from the Village to Central Park, a protest that morphed into New York’s annual Gay Pride Parade.

White Horse Tavern. Image: Elisa.rolle/Wikimedia

Like that of the Stonewall Inn and Julius’, the clientele of White Horse Tavern (Hudson Street at West 11th Street) has changed over time. When the bar opened in 1880, it primarily served the longshoremen who worked on the piers of the Hudson River. By the 1950s labor leaders and left-leaning activists were hanging out here as well, alongside Beat writers and folk musicians. “On the Road” author Jack Kerouac was said to have been kicked out of the bar several times, leading to the graffito “Go home Jack” still visible on the wall of the men’s room. James Baldwin, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Jane Jacobs, Norman Mailer, and Anaïs Nin bent an elbow here as well. The bar is probably best known, however, as being the site of Dylan Thomas’s last hurrah. The Welsh author of “Under Milk Wood” is said to have imbibed numerous shots of whiskey before collapsing just outside the bar; he died several days later of pneumonia exacerbated by his alcoholic lifestyle.

Two of the West Village’s oldest pubs came into their own as speakeasies. 55 Bar

(55 Christopher Street, between Waverly Place and Seventh Avenue South) opened in 1919, just months before Prohibition began. Chumley’s (86 Bedford Street, between Barrow and Grove Streets) poured its first drinks in 1922. Despite predating Chumley’s and operating continuously for more than a century, 55 Bar is less well known, except by music aficionados; it hosts live jazz, blues, or rock music every night.

The entrance to Chumley’s, which in keeping with its speakeasy origins, eschews signage. Image: Beyond My Ken/Wikimedia

While 55 Bar has always been no-frills in appearance—with its worn wood bar, tables, and walls, it could serve as an encyclopedia illustration for “dive bar”—Chumley’s offered marginally more glamour, with a fireplace and wood banquettes occupied by the likes of Willa Cather, e.e. cummings, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ring Lardner, and Eugene O’Neill. Edna St. Vincent Millay even tended bar on occasion. After Prohibition ended, Chumley’s became a restaurant/bar. It retained its literary following, though: When they were not at White Horse Tavern, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Norman Mailer could be found here, as could William S. Burroughs and Ernest Hemingway.

In 2007 the chimney wall of Chumley’s collapsed, After nine years of renovations and red tape, Chumley’s reopened. Oysters, seasonal cocktails, and a dish called Hemingway’s Chili are on the menu, and the wood banquettes have been upholstered in luxe tufted leather. The walls, however, are still adorned not only with photos of past customers but also with scores of book jackets. For decades authors sent Chumley’s a dust cover from the first edition of their books, and Chumley’s proudly displayed them. During Chumley’s renovation the jackets were stored and preserved so that they could once again decorate the walls—a perfect illustration of the West Village’s embrace of its history even as it continues to move forward.